- Home page

- PP Group

- Polish Post

- Our history

From tradition to modernity

For over 466 years, we have been delivering what matters to you, bringing you closer together. We heroically support you in difficult and sad moments. We also accompany you in those filled with joy. Today, we are shortening the distance to deliver parcels to your loved ones in every corner of Poland and abroad. We are always with you where you expect us and when you need us.

466 years with you. Discover our history.

1558

Royal lineage

1647-1772

Mail of elective kings

1795-1918

Under the partitions

1918-1939

Reactivation of the post office after regaining independence

1939

The outbreak of World War II and the defense of the Gdańsk Post Office

1939-1944

Under occupation

1944

Insurgent Post Office

1945-1949

Reconstruction of the postal and telecommunications network in the People's Republic of Poland

1987-2009

Time for change and reform

2012-2018

From tradition to modernity

2021-2024

Digital revolution

1558

Royal lineage

The Polish postal service was established on October 18, 1558, when King Sigismund II Augustus established a permanent postal link between Kraków and Venice via Vienna, using horse-drawn carriages. The main reasons for establishing this new institution were the desire to become independent from the imperial post and the Fugger family's trading post in Augsburg, and to create a permanent information corridor for diplomatic and trade contacts with other European countries.

Many historians believe that the monarch established the postal service to recover the so-called Neapolitan sums, the inheritance of his mother, Bona Sforza, who was poisoned in 1557. The estates Sigismund Augustus sought to recover were transferred, under a forged will, to Bona's debtor, Prince Philip II of Spain. To effectively collect the estate, the king required an efficient communication system. The monarch constantly corresponded with representatives of European courts, seeking support for his cause. Although the inheritance was never recovered, the dispute over the Neapolitan sums lies at the heart of the Polish postal system.

The first administrator of the new postal institution was Prospero Provana, one of Sigismund Augustus's courtiers, hailing from the Italian Piedmont. The newly established institution, modeled on its European counterparts, was to handle both traditional correspondence and the transport of goods and passengers. In its early days, the Polish postal service had a strong royal character. The ruler paid for the messengers, the upkeep of the horses, and the postmaster's salary. Over time, Provana carried out not only the tasks assigned to him by Sigismund Augustus but also orders from merchants and nobles, contributing to the development of the postal system.

An intrigue at the royal court led to changes in the postal administration in 1562. The king dismissed Prospero Provana from his position and entrusted management to Krzysztof Taksis, representing one of the most influential European families, which controlled all international communications. It was during this time that the first reform of the Polish postal system took place, creating the structure we can now call the Polish Post Office.

1647-1772

Mail of elective kings

One of the greatest reformers of the Polish Post Office was King Władysław IV Vasa. He saw great potential in the postal administration and led efforts to develop the institution. The ruler envisioned the post office as a cultural institution that, in addition to disseminating information, also disseminated ideas. On May 2, 1647, the Sejm (lower house of parliament) in Warsaw established a new postal ordinance, obliging cities to pay a quarter of their income to the post office. Władysław IV thus established a fixed postal tax – the quadruple. Ultimately, he wanted to establish post offices in every city with a population of over four thousand. The ruler clearly emphasized the national character of the Polish post office, which, during his reign, ceased to be a royal institution and became a state institution.

During the reign of Stanisław August Poniatowski, the postal service was reorganized. It was based on commercial principles. Postal services became accessible to all, guaranteeing the secrecy of correspondence. Seals and stamps were introduced.

The creation of a regular postal service changed its role. It ceased to be a tool for realizing royal aspirations and became an institution primarily serving the state and its citizens.

The establishment of a postal institution in Poland enabled the Crown to join the network of regular international connections. The development of the administration and subsequent reforms were possible solely thanks to the efficient communication guaranteed by the Polish Post. The granting of state-owned status to the post office permanently established it as an active participant in the revival of independence after 1918.

1795-1918

Under the partitions

On October 24, 1795, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth disappeared from the maps of Europe. The monarchs of the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Austrian Empire carried out the Third Partition of Poland. The postal service then fell into the hands of the occupying powers, serving primarily an administrative function. Polish lands came under the authority of the postal services of the occupying powers, with their respective legal regulations.

The process of organizing the post-partition postal service began in 1807, with Napoleon's establishment of the Duchy of Warsaw. The military postal service began operating at that time, and the first postal boxes appeared on the streets of Warsaw (postal boxes did not become common in Poland until 1854). Political conditions strengthened the importance of connections with Western European countries. As early as 1807, the French Emperor reorganized the postal services in the countries under his control, abolishing the taxi system and territorial communication.

The first administrator of the newly established administration was Ignacy Zajączek. Initially, the post office was an independent institution, reporting directly to Frederick Augustus. Changes in the political situation and the weakening position of the monarch led to the transfer of the postal administration to the Minister of Internal Affairs in 1810.

In the Duchy of Warsaw there were 150 post offices – post offices (post offices) and post stations (post offices and forwarding stations), employing about 1,000 workers (mainly postmasters, postmen and postal workers).

Napoleon's unsuccessful Moscow campaign led to the postal administration in Polish lands coming under the jurisdiction of Prussia.

In 1815, the Congress of Vienna decided to establish the Kingdom of Poland. At that time, the postal service continued in the traditions of Stanisław August Poniatowski and enjoyed full autonomy.

In 1816, there were 178 post offices: 25 post offices and 153 stations. Post offices were divided into two types based on their mode of transportation: regular post offices and special post offices. The first group included foot post offices, delivering correspondence and newspapers on side roads; horse post offices, employing couriers riding on horseback; cart post offices, using a light two-wheeled carriage drawn by a single horse (they transported correspondence and parcels under the care of a postman); and wagon post offices, transporting passengers and merchants. The special post offices were divided into relays – expedited horse post offices (served with priority) and extra post offices, making trips at the special request of travelers.

The postal situation changed after the outbreak of the national liberation uprisings. Postal workers supported the November and January insurgents. The tsarist government decided to incorporate the transportation administration under the authority of St. Petersburg. Transportation in Polish lands operated within the Western Postal District.

It is worth noting that in 1912 there were already almost 800 post offices in the former territories of the Kingdom of Poland.

The Polish Post Office was revived only after Poland regained independence in 1918.

1918-1939

Reactivation of the post office after regaining independence

The beginnings of the Polish postal service after World War I were closely linked to the activities of the Regency Council. By the 1918 decree "On the Temporary Organization of the Supreme Authorities in the Kingdom of Poland," postal operations were subordinated to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Thanks to the actions of the new authorities, who saw the post office as the primary communications agency, the institution acquired a national character.

On February 5, 1919, Chief of State Józef Piłsudski issued a decree establishing the Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs. The Prime Minister, then Prime Minister Jędrzej Moraczewski, appointed Tomasz Arciszewski as the first minister of the new ministry.

When Ignacy Jan Paderewski, returning from the United States, became the new Prime Minister, Hubert Ignacy Linde was appointed Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. The new minister significantly contributed to the reconstruction of the Polish communications system. During his term, numerous international relations were established, local administration was established, continuity of service by operational units was ensured, the scope of services provided by the postal service was established, and postal institutions were established, reporting directly to the new government department: the Postal Savings Bank, the Main Repository of Postal and Telegraphic Materials, the Accounting Audit Office of Posts and Telegraphs, and the Post and Telecommunications Museum.

The early days of Reborn Poland were an extremely turbulent period. Constant armed conflicts and the shifting nature of Poland's borders prevented the systematization of local postal administration. It wasn't until March 1922 that a unified organizational statute was introduced.

On December 5, 1923, the government decided to dissolve the Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs. This decision was conditioned by the country's difficult financial situation. Under the Post, Telegraph, and Telephone Act of June 3, 1924, postal and telegraph affairs were entrusted to the Ministry of Industry and Trade, within which the General Directorate of Posts and Telegraphs was established.

Thanks to the efforts of Marshal Józef Piłsudski's government, the former ministry was revived under the Regulation of the President of the Republic of Poland, Ignacy Mościcki, of January 19, 1927, establishing the office of Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. The Polish Post strengthened its position and entered a new phase of its operations.

1939

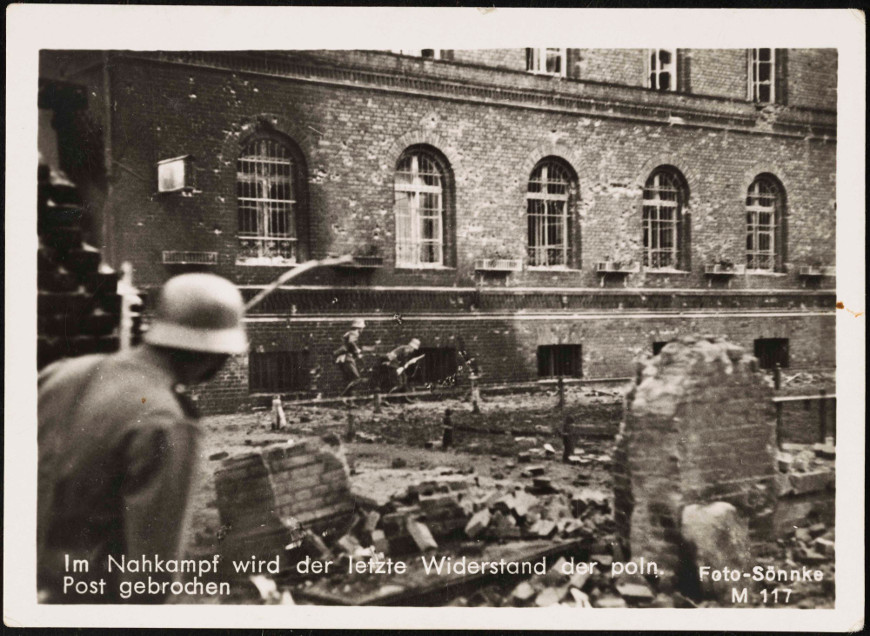

The outbreak of World War II and the defense of the Gdańsk Post Office

Under the Treaty of Versailles, the Polish Post Office had a post office in the Free City of Danzig at Hevelius Square. It housed, among other things, a telephone exchange with a direct line to Poland. It is estimated that in September 1939, the Gdańsk branch of the Polish Post employed just over 100 people. Most postmen belonged to a Polish paramilitary organization, the Riflemen's Association. Within this organization, and in accordance with its organizational charter, they received combat training at courses in Poland. In April 1939, command was assumed by Second Lieutenant Konrad Guderski, sent to Gdańsk by the General Staff of the Polish Army. He oversaw additional combat training for the postmen and prepared the building for defense. To this end, trees surrounding the post office were cut down and the entrance to the building secured. In mid-August, the post office staff was reinforced with ten employees, seconded from branches in Gdynia and Bydgoszcz.

The attack on the Polish Post Office began at 4:45 a.m., simultaneously with the battleship Schleswig-Holstein's bombardment of Westerplatte. Earlier, around 4:00 a.m., the building had been deprived of electricity and all telephone connections.

The attacking German forces included a special unit of the Gdańsk Order Police (Schutzpolizei) and subunits of the SS Wachsturmbann "E" and the SS-Heimwehr Danzig. These units, in addition to small arms, had three ADGZ armored cars at their disposal. The attack was commanded by SS-Untersturmführer Alfred Heinrich.

At the time of the attack, 43 postal workers from the Polish Post Office were in the building, along with 10 postal workers delegated from Gdynia and Bydgoszcz, and one Polish railway worker from Gdańsk. They had three Browning model 1928 light machine guns, pistols and rifles, and a number of hand grenades. Also in the building were the caretaker, his wife, and their 10-year-old daughter. The workers, who were scheduled to start work at 8:00 a.m., were stopped by a police cordon in front of the building.

According to assumptions developed by the Polish Army General Staff, the postmen were to hold out for approximately six hours, until separate subunits of the "Pomorze" Army arrived to relieve them. Unlike the commander of the Westerplatte garrison, the postmen were not informed of the Intervention Corps' withdrawal from Pomerania, nor were their defense orders canceled.

The first German attack ended in failure; they were repelled. During this attempt, its commander, SS-Untersturmführer Alfred Heinrich, was mortally wounded. Simultaneously, an attack from the direction of the Employment Office was repelled, where holes had been punched in the walls. Here, in turn, the defense commander, Second Lieutenant Konrad Guderski, was killed (by the explosion of his own grenade, which he used to eliminate a group of Germans attacking through a hole in the wall).

Around 11:00, the German attacking forces were reinforced with two light 75 mm guns. Despite this, the second attack also ended in failure for the attackers.

Around 3:00 PM, the new German commander of the attack ordered a pause in the assault and gave the postal workers two hours to surrender. Simultaneously, a 105 mm howitzer was brought in, and sappers dug a tunnel under the post office wall, where they planted a 600-kilogram explosive charge. After the ultimatum expired (at 5:00 PM), the charge was detonated, demolishing part of the building's wall, and German troops, supported by three artillery pieces, launched an assault, capturing part of the post office building. During this time, the defense was limited to the basements, where the defenders had taken shelter from the shelling.

Around 6:00 PM, motor pumps were brought to the post office and the Germans pumped gasoline into the basements, which they then ignited with flamethrowers. As a result, five postal workers were likely burned alive.

At 7:00 PM, the defenders decided to surrender. The first to emerge from the burning building was Director Dr. Jan Michoń. Despite carrying only a white flag, he was shot by the attackers. Following him, Postmaster Józef Wąsik was burned alive with a flamethrower.

Six postal workers managed to escape from the building. Two of them were arrested on September 2nd and imprisoned with the other defenders; the remaining four managed to escape and survive the war. The remaining defenders were arrested and initially placed in the Police Presidium building in Gdańsk (28 people), while the wounded and burned (16 people) were taken to the city hospital. Of those sent to the hospital, six died from their injuries. The youngest victim of the attack on the post office was 10-year-old Erwina Barzychowska, a child of the caretaker and his wife. Severely burned by a flamethrower while attempting to leave the post office building, she died in hospital seven weeks later.

1939-1944

Under occupation

With the outbreak of war, civilian communications were subordinated to the national defense system. By September, telecommunications services were provided by 43 regional telephone and telegraph offices, six radiocommunications offices, approximately 240 telecommunications supervisory offices at regional offices, and the Central Telecommunications Office in Warsaw. Already in the first days of World War II, communications officers were engaged in combat. The defense of the Gdańsk Post Office and their fights in the defense of Warsaw and the Modlin Fortress are particularly noteworthy.

Following the September Campaign, the General Government was established from the territories of central and southern Poland, establishing German administrative order. By decree of Governor Frank in October 1939, the German Post Office East (Deutsche Post Osten) was established, taking over all assets and rights of the Polish Post Office. Third Reich postal and telegraph law applied to its offices. The sending of letters to civilians via the German post office did not resume until mid-November 1939. Correspondence was subject to censorship.

During World War II, the Polish Post Office resumed operations in Great Britain. In April 1941, negotiations were initiated with the British Ministry of Internal Affairs regarding the issuance of postage stamps by the Polish government, and legal regulations for our postal operations were initiated. Under the provisions of the International Postal Convention, the Polish government had the right to establish offices on merchant ships and warships within Polish territory. Maritime postal agencies delivered correspondence to addressees in Great Britain, friendly countries, and neutral countries. In July 1945, following the liquidation of the Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Shipping, postal agencies on warships and merchant ships ceased operations.

In late 1940, the government in London appointed a Chief Delegate for Poland, charged with establishing and expanding the underground administration. The envoy carried out his duties through a delegation divided into several departments, including the Post and Telegraph Office, whose structure was based on the pre-1939 organization of the Polish Post Office and Telegraph Service. During the Nazi occupation, the Polish Post Office was a secret organization, a military institution that did not serve the civilian population. Only during the Warsaw Uprising was it allowed to operate as a public utility. The command entrusted its operation to the Scouts. Losses to the Communications Ministry resulting from the war on Polish soil were estimated at over one billion pre-war złoty. Over 70% of the post office network was destroyed, while 79% of the post and telecommunications buildings, lines, and equipment were destroyed, and 90% of the transport vehicles were also lost.

1944

Insurgent Post Office

The history of the Scout Field Post (HPP) is closely linked to the activities of the Home Army Field Post. Clandestine communications within the Underground State were among the most extensive among the underground organizations in occupied Europe.

Pasieka, or the Grey Ranks Headquarters, was where the Scout Field Post began its operations. On August 6th, the HPP was officially established in its first branch at 41 Wilcza Street.

Pursuant to an agreement between the Head of Scouting Headquarters and the Warsaw District of the Home Army, the Main Scout Post Office and its posts were established in the liberated districts of the city. Postcards were introduced into circulation, and letters were accepted unsealed, date-stamped with the Polish Post Office stamp, and censored, delivered to their addressees. Order No. 14 issued by the commander of the Uprising, General Antoni Chruściel "Monter," on August 11, stated, among other things: "On the 6th of this month, at the initiative of the Scouts, a field post office was launched... Field post office is subject to military censorship... The entire content of correspondence should not exceed 25 words.

The shipments were handled free of charge. However, civilians often exchanged the letters they received for food or clothing, which the Scouts then delivered to those most in need.

Parallel to the HPP, the Home Army Field Mail was being established, headed by Major Maksymilian Broszkiewicz, codename "Embicz," who had many years of experience as a postman and communications officer. On August 30, 1944, by order of Colonel Chruściel, codename "Monter," the Scouts' communications service was formally incorporated into the structures of the Home Army Field Mail.

Despite the lack of precise data on the efforts of the field postal service (HPP and PP AK), i.e., the number of parcels dispatched, it is estimated that HPP postmen delivered 200,000 parcels during the Warsaw Uprising. According to these estimates, the postal service delivered approximately 6,000 letters daily.

1945-1949

Reconstruction of the postal and telecommunications network in the People's Republic of Poland

Due to the fact that the issue of Poland's western borders remained unresolved until July 1945, the opening of post offices could not precede the activities of official offices and institutions of the Polish authorities.

By the end of December 1944, the total number of offices in the country reached 614, including 382 agencies and 232 offices. The Lublin district had the largest number, reactivating 14 regional offices. On September 1, 1945, the scope of services was expanded to the pre-September 1939 level.

In the immediate postwar years, virtually no post office had date stamps, sealing machines, or stamps. Pre-September official seals with a crowned eagle, German postal stamps, and rubber stamps with the office's name were used. The mailing date was handwritten. There was also a shortage of stamps, so postal services were paid for in cash.

Due to the destruction of roads, bridges, and railways, the fastest means of delivering parcels was by civilian aircraft. Unfortunately, these operated only between larger cities. For shorter routes, cars and motorcycles were used. As the repaired railway lines were opened to the public, ambulance services and postal-rail convoys were gradually introduced. The first such services began on August 16, 1944, on the Lublin-Rozwadów route.

The main task of the Polish Post until 1945 was to rebuild the communications network and achieve the pre-war level of services.

1987-2009

Time for change and reform

A turning point in the company's operations came in 1987. PPTiT became an independent entity with nationwide reach. Communications became fully autonomous, and cooperation with the General Directorate was to be based on civil law provisions and the operation of economic mechanisms. From then on, PPTiT was to operate as a multi-plant enterprise.

On December 29, 1988, the Minister of Transport, Navigation, and Communications approved the statute of the state entity, regulating its operations within a new organizational structure. Under the amended rules, the Director General (appointed by the minister) represented the enterprise externally and determined its internal structure and tasks.

In 1991, the Polish Post and Telecommunication separated. Thus ended the shared history of the state-owned entity: Polish Post, Telegraph, and Telephone. In the following years, the Post operated as a State Public Utility Company, before transforming into a joint-stock company in 2009, fully owned by the state treasury.

Operating in a liberalized market proved to be the biggest challenge for Poczta Polska. New courier service providers emerged, and on January 1, 2013, Poczta Polska's monopoly on shipments weighing less than 50g was abolished.

2012-2018

From tradition to modernity

The 21st century has brought new challenges to the postal market. The phenomenon of e-substitution, or the use of electronic forms of communication, has forced all postal services worldwide to redefine their strategic goals. These are times when services must adapt to the needs of customers who use the internet daily.

In 2012, Poczta Polska Usługi Cyfrowe (Polish Postal Services Digital Company) was established. Between 2013 and 2014, it launched products such as neocards, neoletters, neostamps, and neoinvoices. This makes most traditional postal services available electronically and online. Poczta Polska also offers electronic solutions for traditional letter and parcel services, such as electronic advice notes, the ability to design your own stamp, and online parcel shipping.

In recent years, Poczta Polska's main strategic focus has been the development of courier services. This is a nod to customers involved in e-commerce.

The external symbol of the changes taking place at Poczta Polska is the new visual identity of its branches. Poczta Polska has changed its color scheme – from blue to red and gold – in keeping with the tradition of the Royal Mail. The company has also begun a process of changes to its network of post offices. New branches are being built according to a standard encompassing uniform colors, design, finish, and functionality. They have separate zones: postal (letters, parcels, deposits and withdrawals), banking and insurance (accounts, deposits, policies), and retail (e.g., postcards and newspapers). Larger branches also feature self-service zones with devices for sending and receiving mail.

In an era of shifting away from traditional correspondence and increasing digitization, Poczta Polska is focusing on strengthening the most promising areas – parcels, logistics, finance, international services, and services provided to public administration. In accordance with the decision of the Economic Committee of the Council of Ministers in June 2018, Poczta Polska is a partner for public administration in preparing for the provision and implementation of electronic and hybrid correspondence delivery services for public administration (e-Delivery).

2021-2024

Digital revolution

In October 2021, Poczta Polska launched the Public Registered Electronic Delivery Service (PURDE) and the Public Hybrid Service (PUH). Since then, it has continued to provide services to entities with active electronic delivery addresses (ADE), in accordance with applicable regulations and requirements.

The advantage of e-Delivery is access to all official documents in one secure place. This is achieved through the Delivery Box (SD), which can be personal, business, or dedicated to businesses, depending on your needs. Anyone interested in using e-Delivery can choose to authenticate to the service using a trusted profile, e-ID card, or mObywatel.

The rapid exchange of electronic official correspondence is possible thanks to the Electronic Delivery Address (ADE). To obtain an ADE, you must submit an application to the Minister responsible for IT. This can be done online at gov.pl. Once the ADE is created, all that remains is to activate it, provide an email address for notification, and fully enjoy all the benefits the service provides.

Since 2023, Poczta Polska has been offering Q-Delivery (renamed e-Poleconyin 2024), a new service offered as part of e-Delivery, or registered electronic delivery. Non-public entities, such as companies, entrepreneurs, associations, attorneys, and individuals, can use e-Registered to communicate with each other. Previously, the public service of registered electronic delivery could only be used for communications with public entities – public authorities, including local governments.